2.1 Global drug trafficking shifts to a duopoly

Drug markets have been undergoing profound transformations, driven by major shifts in the global criminal economy. Disruptions in Afghan heroin production, surging cocaine supplies, the steady rise in the market for synthetic opioids, and the partial legalization of cannabis in some countries are reshaping patterns of production, trafficking and consumption worldwide.1 As the dynamics of the drug markets change, the consequences for public health, organized criminal activity and drug-related violence are becoming increasingly severe.

The result is a steadily expanding global drug trade, marked by record-high drug use and mounting social and security costs in nearly every region. The 2025 World Drug Report estimates that 316 million people used drugs in 2023 – a 28% increase over the past decade, outpacing global population growth.2 Beneath this overarching trend, distinct dynamics are emerging that will shape the contours of the drug economy in the years ahead.

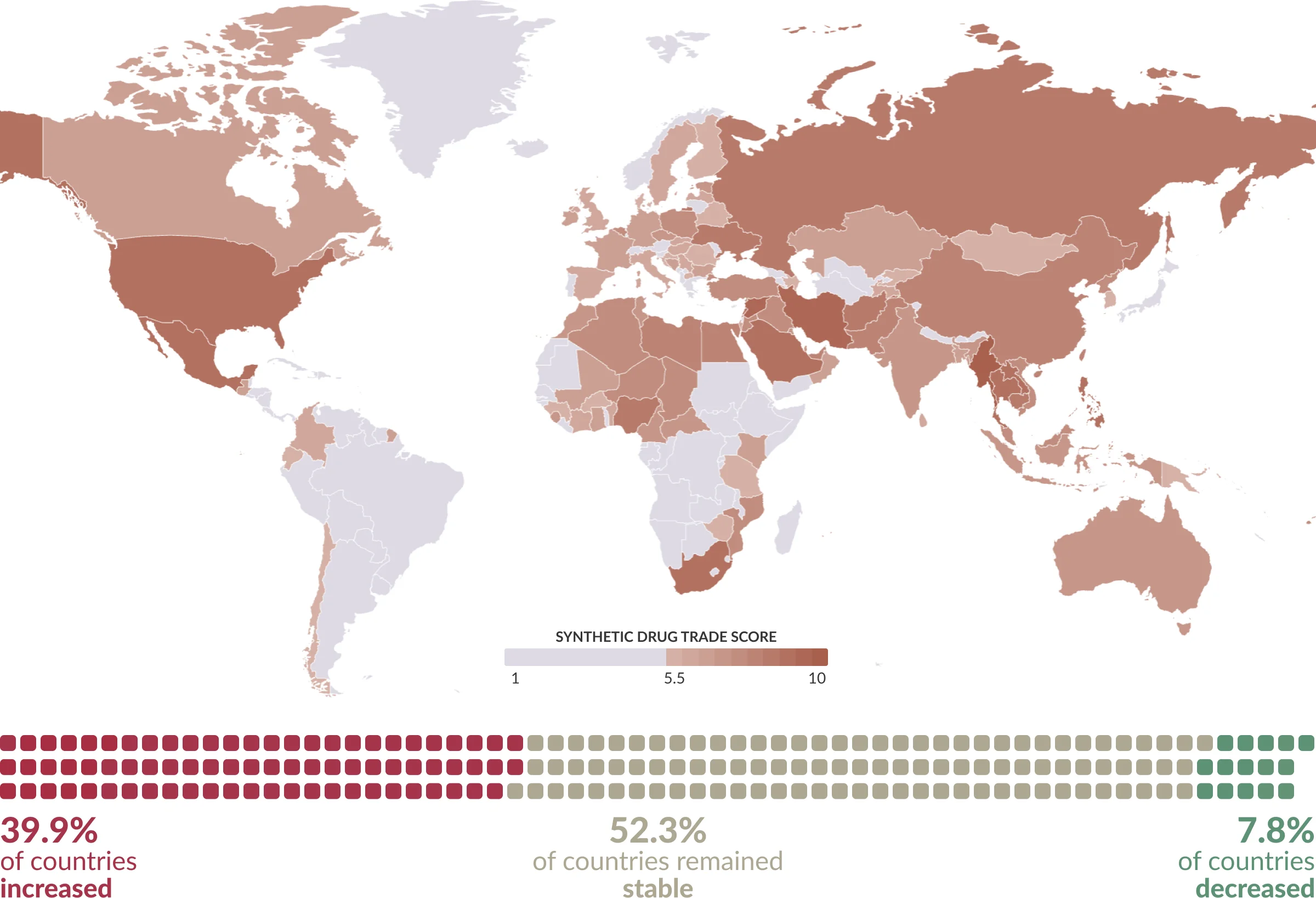

A key shift is the sharp rise in the prevalence of cocaine and synthetic drugs, which have steadily expanded in influence and availability since the first global assessment in 2021. Both markets have shown continuous and substantial growth in their scores. Cocaine rose from 4.52 in 2021 to 4.89 in 2025 (+0.37); synthetic drugs increased more markedly, from 4.62 to 5.14 (+0.52) over the same period. Notably, the synthetic drug trade also registered the largest year-on-year increase of any criminal market since the 2021 edition of the Index, second only to financial crimes since 2023.

Drug markets (2021–2025)

While cannabis remains the most widely used illicit substance (ranking as the fourth highest-scoring criminal market in the latest iteration, at 5.19) and heroin, despite an overall slowdown, continues to hold ground in certain regions, the 2025 Index highlights a turning point: cocaine and synthetics, though not yet the most prevalent, are on a rapid path to dominating global drug markets. This shift reflects their profitability and adaptive nature – seen in how criminal actors capitalize on changing consumer preferences, advances in production and increasingly interconnected trafficking networks.

However, cocaine and synthetics follow different patterns. Cocaine production is highly localized, tied to specific geographic and climatic conditions, and with supply chains controlling smuggling routes and logistical infrastructure. Production demands specialization, allowing large cartels and powerful criminal organizations to dominate and exert control over territories.3

The cocaine market is a testament to the global reach of South America's drug cartels, which maintain connections with local groups in other regions to facilitate this illicit trade.4 The regional concentration is reflected in the Index scores, with South America (8.42), Central America (7.94) and the Caribbean (6.81) ranking highest in the world for the cocaine trade. West Africa and Western Europe follow closely (at 6.67 and 6.05, respectively), as cocaine flows to Europe – directly or via Africa – have surged in recent years.5

Cocaine trade by region (2025)

In contrast to the cocaine trade, the synthetic drug economy is far more flexible and decentralized. Production laboratories can be set up anywhere close to consumer markets, lowering operational costs and production barriers.6 The trade in precursor chemicals is also difficult to regulate, as many of the input chemicals used to produce synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine and synthetic opioids are legally retailed and widely accessible.7 This versatility makes the market difficult to control and highly adaptable. According to the Index, synthetic drugs exert significant to severe influence in around 50% of countries in the study,8 with 77 out of 193 experiencing an expansion in their synthetic drugs market since 2023.

The pervasiveness of the synthetic drug trade

North America (7.75) faces a deepening crisis driven by fentanyl and methamphetamine,10 while Western Asia (7.54) remains heavily affected by Captagon, which continues to circulate widely despite political change in Syria11 and increasingly overlaps with methamphetamine networks.12 South-eastern Asia (7.41) is another major hub, sustaining vast methamphetamine production and exports.13 Meanwhile, Pacific and Oceanian countries serve as transit points between the Americas, Oceania and Eastern Asia. At the same time, synthetic markets are spreading into new geographies: in West and Central Africa, the non-medical use of synthetic pharmaceuticals such as tramadol is a growing concern, while the emergence of highly potent opioids like nitazenes in parts of Europe signals an escalating and diversified challenge.14

Synthetic drug trade by region (2025)

The rapid market growth in synthetic drugs and cocaine sheds a light on how drug economies can become particularly pervasive, albeit through very different means. The emerging duopoly of cocaine and synthetic drugs, however, does not mean that heroin and cannabis have lost their significance in the global drug economy. Cannabis, in particular, remains the most widely consumed drug, driven by a combination of social and cultural factors, as well as its less harmful effects in comparison to other controlled substances. It continues to rank among the most traded illicit commodities worldwide, largely because of its low cost and ease of production, and has been identified as the most pervasive drug market globally across the three Index editions. Despite a global decline from 5.34 in 2023 to 5.19 in 2025 (−0.15), it still remains above the 2021 level of 5.10.

However, the status of the drug is evolving as legal and reform frameworks are reshaping the cannabis market. Increasingly permissive legal environments – particularly in North America, Europe and Latin America, where a growing number of countries are progressively decriminalizing or regulating cannabis for non-medical use – are creating opportunities for licit markets to grow, even as illicit trade remains significant.15 This coexistence of legal and illegal markets underscores the complex relationship between regulation and organized crime. While regulation or legalization can weaken certain criminal economies, it can also drive criminal actors to trade in other, often more harmful, commodities, requiring authorities to adapt their responses and focus on emerging drug-related threats.16

Similarly, heroin remains widely available, especially across Asia, with a continental average of 5.28, far higher than any other region globally. Although opium production has dropped following the 2022 ban on poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, the market has shown a degree of stability in certain regions, sustained by reportedly abundant stockpiles and alternative sources, such as opium cultivation in Myanmar.17 Recent police operations in European countries revealed that heroin continues to be transported hidden in trucks and cars along traditional pathways through Central Asia and the Balkans, as well as along less usual trafficking routes. Yet, signs of gradually reduced purity and rising prices suggest a diminishing supply.18 Reflecting this, the heroin market recorded the steepest decline of all criminal market indicators in the Index, falling from 4.08 in 2023 to 3.77 in 2025 (−0.31). This indicates that, although stockpiles are still being drawn on and trafficking routes are adapting, signs of shortages are emerging, raising the risk of a shift toward synthetic opioids as substitutes, as highlighted above.

With synthetic drugs already expanding globally at an unprecedented pace, and the heroin trade now assessed as the least pervasive criminal market worldwide, the development of new alternative substances points to a major structural change in drug markets. This shift warrants close attention, not only because of its potential to reshape trafficking dynamics, but also because of the significant public health risks it poses, underscoring how quickly synthetics can gain ground wherever demand exists.

2.2 Forms of non-violent organized crime are exerting a growing impact, adding to the burden of enduring violent crimes

Violence is a recurrent feature of organized crime. Its role, however, varies depending on the criminal market. In some cases, violence is ancillary, in that it is used as a supportive tool but is not strictly necessary to sustain the underlying illicit activity. In others, violence (or the credible threat of it) is intrinsic to how the market operates, and is strategically deployed to achieve a criminal group's goals, enforce internal rules or settle disputes with rivals.19 This distinction is important, as not all forms of organized crime rely on violence to the same degree.

There are some markets that are inherently less violence-prone. Cyber-dependent crimes and financial crimes operate through technological means, manipulation and fraud rather than physical coercion. These markets highlight the growing importance of 'invisible' forms of organized crime. Less reliant on traditional violent methods, they are more dependent on the transnational financial and digital systems that facilitate the global flow of money, and are often harder to detect.

That is not to say that violence is completely absent in these sectors, particularly when they intersect with more conventional criminal activities. A notable example of this can be found in the scam centres proliferating across South-eastern Asia, especially in Myanmar. Here, victims lured by fraudulent job offers are trafficked to hotels and casinos repurposed as compounds for scam operations. Once inside, they are subjected to threats, physical abuse and sexual exploitation, or forced to work under coercive conditions to carry out crimes (most often online fraud) targeting victims worldwide.20

However, when we think of financial and cyber-dependent crimes, such as ransomware, DDoS attacks, online scams, phishing and identity theft, we typically perceive them as virtual, non-violent and non-territorial activities, and relatively less harmful than other criminal economies.21 Although this may be generally true in terms of the physical harm accompanying these activities, it is not the case when considering psychological impact, reputational damage and financial loss. INTERPOL estimates that the total value lost to cybercrime yearly now rivals the GDP of major economies.22 With costs projected to more than double in the coming years, the financial toll is not only accelerating but also fuelling a shadow economy that sustains further criminal innovation and draws more actors into illicit activities.23 The accessibility of cybercrime markets is a fundamental driver of their expansion. Off-the-shelf tools, such as pre-packaged commercial hacking kits, and outsourced services can be obtained relatively easily, lowering the barriers to entry and enabling individuals with limited technical skills to carry out sophisticated attacks.24

Criminal market changes (2023–2025)

In terms of global pervasiveness, financial crimes remain the most prevalent criminal market in 2025, with a score of 6.21. Of the 15 markets measured by the Index, this market also saw the greatest expansion since 2023 (+0.24, up from 5.98) and is the only market indicator consistently ranked among the top five in all continents (taking the top spot in both Africa and Europe). This extensive global scope reflects not only the wide spectrum of crimes encompassed within the financial crimes category – from traditional offences, such as embezzlement and tax evasion, to sophisticated cyber-enabled schemes like online scams and business email compromise – but also its growing appeal, as it is generally perceived as a low-risk, low-cost form of crime. Notably, 78 countries recorded worsening financial crime markets since 2023.

Changes in financial crimes market (2023–2025)

Cyber-dependent crimes, although among the less pervasive markets globally, also registered growth (+0.09, rising from 4.55 to 4.65). More regions (18 out of 22) experienced a worsening of their cyber-dependent crime markets than of any other category, underscoring its expanding global footprint. The regions most affected by cyber-dependent crimes vary widely in their economic and socio-political contexts.

Regional changes by criminal market (2023–2025)

Cyber-dependent crimes had high scores in North America and Australia and New Zealand (both regions at 7.50),25 Eastern and South-eastern Asia (respectively at 6.50 and 6.41), as well as Northern Europe, and Central and Eastern Europe (both at 6.0). This shows that the prevalence of cyber-dependent crimes is independent of geography, level of economic development or position along criminal supply chains, with both source and target countries equally vulnerable. According to the 2024 Global Risks Report of the World Economic Forum, attempts to use technology to disrupt critical resources and services are expected to become more frequent and dominate global concerns over the next decade.26

Financial crimes and cyber-dependent crimes by region (2025)

These crimes represent an escalating threat, not only because of their growing prevalence, but also because evidence suggests that national resilience measures are insufficient to meet the challenge. The relative lack of violence associated with such forms of crime may render their impact less immediately visible, yet their consequences are often more far-reaching, undermining both economic stability and national security. Although some countries are improving measures to confront cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled crimes – strengthening national policies and laws, often using the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime (also known as Budapest Convention)27 as a guideline, creating specialized cybercrime units, fostering public–private partnerships and raising awareness of cybersecurity – many still lack the technological infrastructure and capabilities needed to detect, prevent and disrupt such crimes.28 In these settings, regulatory frameworks are often fragmented, detection systems weak, reporting mechanisms underdeveloped and data collection typically insufficient. These gaps create fertile ground for criminal actors to exploit.29

Statistical analysis based on the 2025 Index results reveals a weak correlation between financial and cyber-dependent crimes and overall resilience (−0.240 and +0.324, respectively). In other words, resilience efforts made in the political, criminal justice, economic and social spheres appear to have only a marginal impact on these markets. This is partly explained by the nature of financial and cyber-dependent crimes, which, as explained, involve intangible commodities, such as data, digital platforms or financial systems, and generally do not rely on physical violence. As a result, they are relatively easy to perpetrate yet very difficult to detect, investigate and police. At the same time, the findings highlight that current responses remain inadequate and insufficiently effective in addressing fast-growing forms of organized cybercrime, such as online fraud and cyber-attacks.

Correlation coefficients between resilience and financial crimes, and cyber-dependent crimes (2025)

While some countries have begun to integrate such strategies, they are limited in scope and uneven, generally directed at traditional, and often more visible, forms of organized crime. This underscores that the fight against financial and cyber-dependent crimes is not keeping pace with the markets. Even highly developed countries in Northern Europe, such as Denmark and Sweden, despite having strong legal frameworks and advanced cybersecurity infrastructures, are vulnerable and frequently targeted by cyber-threats. Both countries score 6.50 for cyber-dependent crimes, reflecting a market of significant influence, even though their resilience frameworks are assessed as relatively strong, averaging 8.21 and 7.38, respectively. Unless resilience measures are recalibrated to address emerging risks, resilience frameworks risk losing relevance and effectiveness in the face of these forms of crime.30

If the growing global prominence of financial and cyber-dependent crimes constitutes a troubling trend, and one that signals a profound shift likely to shape the future of organized crime, the persistence of more traditional, violent forms, even if declining in some contexts, remains significant. Violence, albeit not inherent, can be critically instrumental in many illicit markets. In drug trafficking, for instance, violence continues to play a central role at strategic transit points and logistical hubs, where violent control of supply chains and competition are intense. Similar dynamics are found in human trafficking, where violence, intimidation and debt bondage are used to control victims, and in markets such as oil theft or diamond and wildlife smuggling, where force can secure access to resources.31

Yet the markets considered to be most intrinsically linked to violence are extortion and protection racketeering, and arms trafficking. Extortion schemes rely heavily on intimidation and coercion, with violence serving as the main tool through which organized crime groups establish and maintain territorial control, extract payments from businesses or individuals, and sustain reputational dominance.32 In the case of arms trafficking, the relationship between violence and organized crime is even more direct. Firearms are not only traded commodities but also essential enablers of crime, conflict and insecurity. Illicitly sourced weapons are crucial tools for organized crime groups, enabling them to intimidate, coerce victims and engage in other crimes. This is especially true in already insecure environments, where the illicit flow of weapons can prolong and intensify organized crime and armed conflicts, and their presence among civilians can hinder peacebuilding efforts and undermine security.33 This link is underscored by the fact that arms trafficking has the highest correlation with the 2025 Global Peace Index's safety and security domain, at 0.67.

In today's world, marked by geopolitical tensions, violent confrontations and inter-state conflicts, one might expect criminal markets most closely intertwined with violence to have grown in pervasiveness in the 2025 Index. Yet, both the extortion and arms trafficking markets recorded a slight decline at the global level (−0.10, from 4.02 to 3.92, and −0.02, from 5.21 to 5.19, respectively). While this may seem counterintuitive, the declines are only marginal in numerical terms, especially given the Index's global scope of 193 countries, each with its own distinct geographic and socio-political context. Indeed, the pervasiveness of such markets differs greatly when we examine the specific local contexts in which they operate.

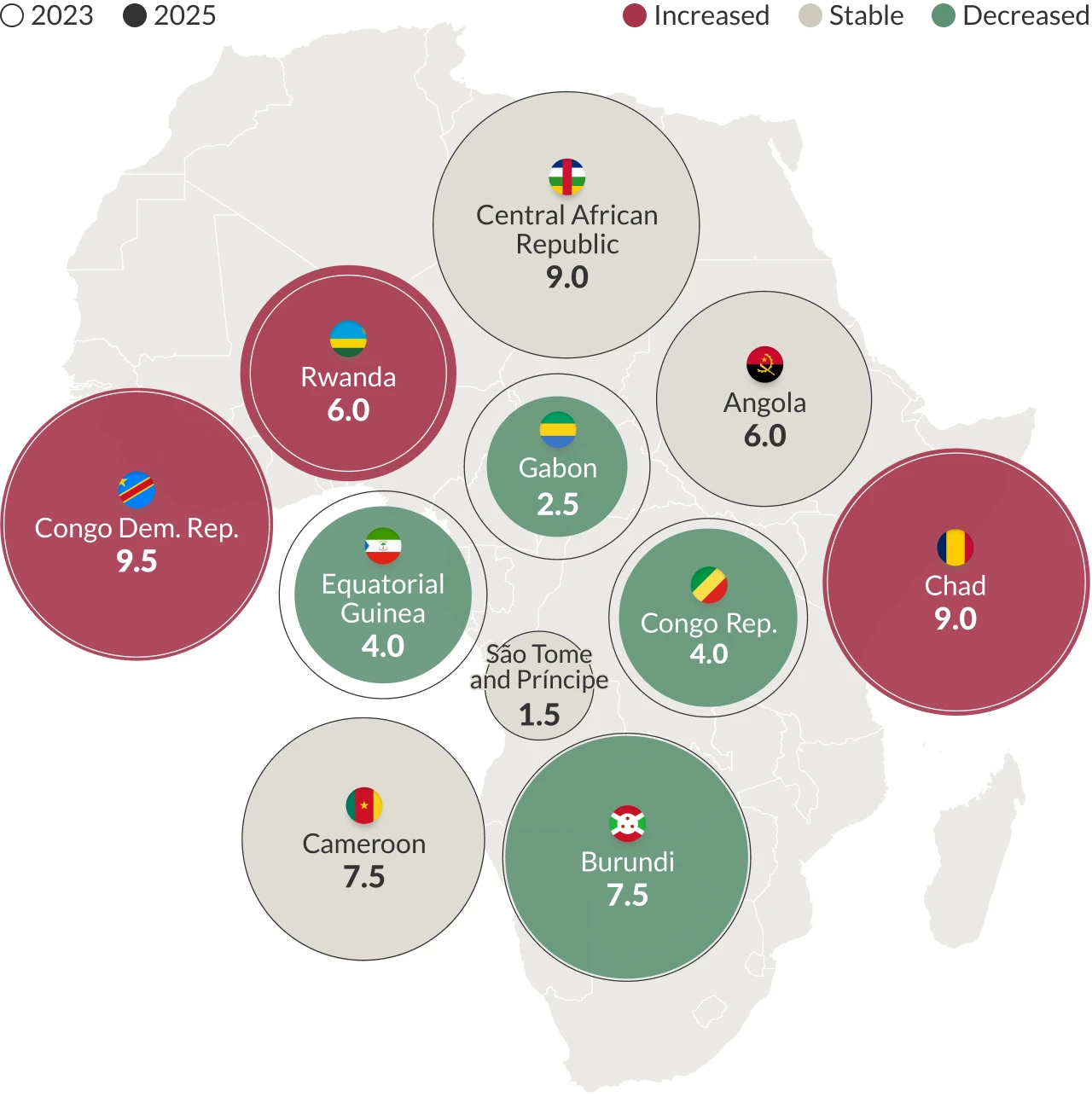

For instance, the regional average for arms trafficking in Central Africa fell by 0.27 between 2023 and 2025, though the region remains among the world's highest-scoring for this market (at 6.05). At first glance, this seems surprising given the highly volatile situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)34 and other countries in the region, such as Chad, which has become deeply affected by spillover effects from the war in Sudan and rising cross-border demand for weapons.35 However, a closer look reveals a more nuanced picture: the DRC and Chad both recorded score increases (+0.50 each), while the average regional decline is explained by countries such as Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, where improvements in security measures and arms monitoring have reduced trafficking risks following past periods of heightened instability.36

Arms trafficking score changes, Central Africa (2023–2025)

Several other dynamics are also at play. The world has become increasingly insecure, with calls for increased militarization, and at the same time several recent conflicts have been primarily state-based and fought with advanced military technologies (drones, ballistic missiles and heavy weaponry), which are difficult for non-state actors to acquire through illicit channels. These arsenals are typically sourced through formal procurement contracts with foreign suppliers, sometimes controversial from a human rights perspective, but nonetheless licit.37

That said, risks remain. Weapons acquired legitimately can leak from state stockpiles and find their way into criminal networks, but such diversions often take time to materialize and are highly context-dependent, shaped by factors such as stockpile management, border controls and oversight mechanisms. Ukraine illustrates this complexity: despite concerns about the diversion of small arms and light weapons from the battlefield into Europe, no evidence of widespread trafficking into the EU has yet emerged.38 The potential for criminal groups to exploit such contexts remains, however, making close monitoring of supply chains and trafficking routes essential.

As for extortion and protection racketeering, recent trends suggest a gradual shift away from more overt forms of violence. In several contexts, criminal groups appear to rely less on direct physical aggression, instead entrenching themselves within political and economic systems, where they advance their activities through corruption and fraud.39 This reduces their visibility while allowing them to maintain control, illustrating how criminal organizations can adapt their strategies to sustain influence without attracting excessive pressure from enforcement agencies. However, while this may hold true in some country contexts, in others – particularly in Central and South America – the violence associated with groups engaged in extortion remains a serious concern. Victims still face brutal intimidation, including killings, which fuels insecurity and sows fear.40

In sum, these dynamics show that another change in the way organized crime markets operate is underway. While violence continues to play a critical role in enabling organized crime in many regions and sectors, its role is diminishing in some contexts as less physical and less violent, but nevertheless equally harmful, forms of criminality gain ground. As global connectivity deepens and digital ecosystems grow more complex, opportunities for exploitation multiply. This is driving cyber-dependent crimes and financial crimes, particularly those cyber-enabled forms like online fraud that digital tools amplify.41 The challenge is compounded by the difficulty many countries face in crafting and implementing effective responses to these emerging 'non-violent' threats. Taken together, the changing dynamics show that cybercrime is no longer a peripheral concern but a central, rapidly escalating threat to global stability.

2.3 Counterfeiting at a crossroads: growth in an unstable global economy

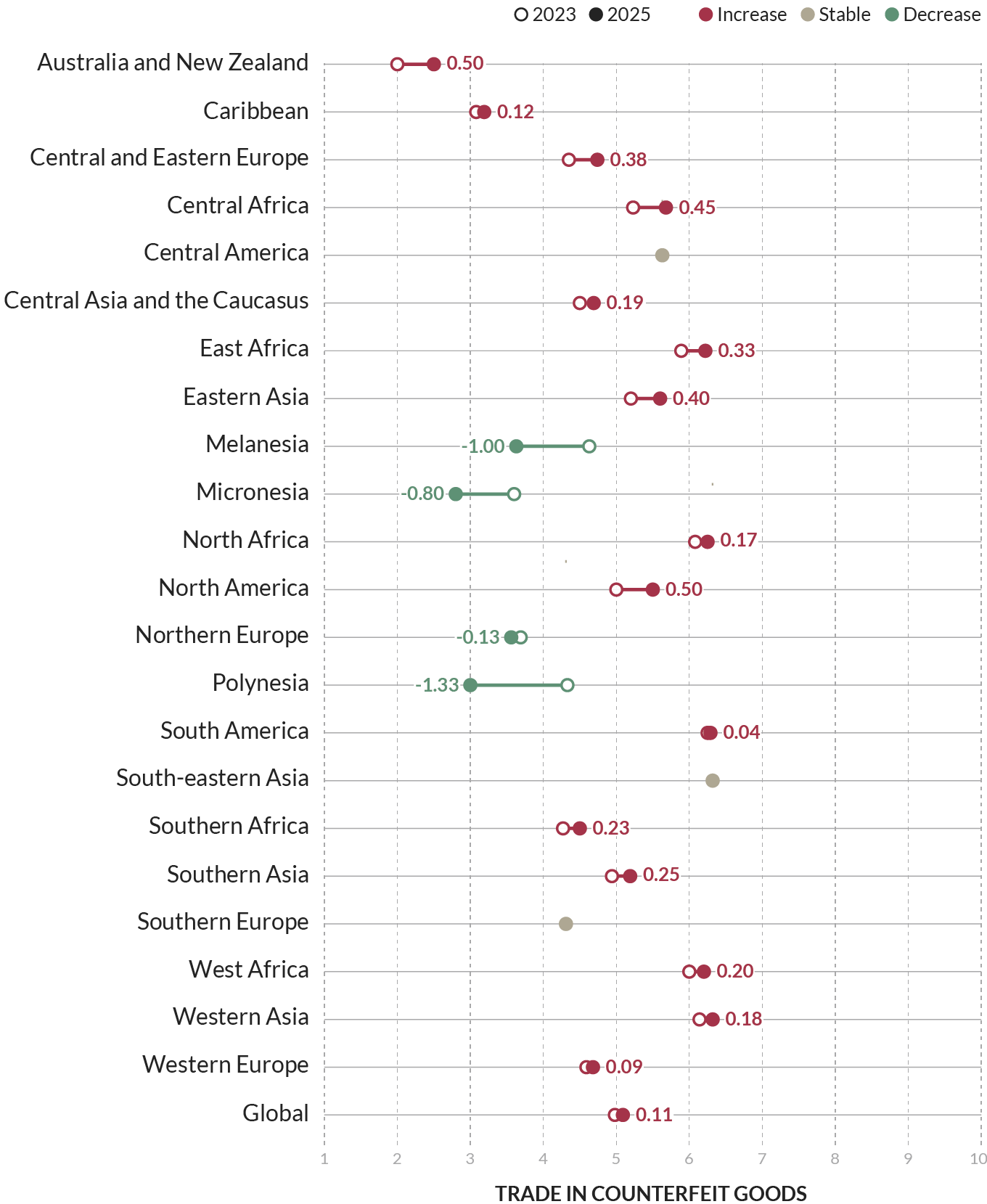

The trade in counterfeit goods, a market that was first incorporated into the Index data in 2023, continues to occupy a mid-tier position among the 15 criminal markets. Averaging 4.98 in 2023 and rising to 5.09 in 2025, the counterfeit goods market has grown but remains within the middle range of global pervasiveness. This ranking, however, has contributed to a tendency to overlook counterfeiting relative to other illicit markets. This market has long escaped the attention of policymakers, law enforcement and researchers, even as its scale and visibility have begun to expand rapidly, particularly through digital platforms and social media channels, which provide counterfeiters with global reach at minimal cost.

Criminal market evolution (2021–2025)

The stereotypical perception of counterfeit goods as the occasional fake handbag smuggled back from a holiday trip no longer reflects reality. The market has diversified and industrialized, encompassing everything from luxury items and everyday consumer goods to life-saving medicines. New data highlights the magnitude of the problem: the European Union Intellectual Property Office and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates placed the value of the counterfeit trade at US$467 billion in 2021,42 with projections reaching US$1.79 trillion by 2030.43 Besides substantial economic loss in the form of reduced revenues for legitimate companies and forgone tax income for states, the counterfeiting market has other sinister implications. It undermines formal market structures, erodes consumer trust in brands and, in more severe cases, endangers public health. Counterfeit pharmaceuticals and electronics, for example, have been associated with health complications, such as injuries, and in extreme cases, fatalities.44

This steady growth in counterfeiting is closely tied to technological innovation, which has radically lowered barriers to entry for illicit actors. Digital commerce platforms have become the dominant arena for counterfeit transactions, where goods can be advertised and purchased with anonymity. Payment systems increasingly rely on non-traditional methods, including digital wallets and cryptocurrencies, which obscure financial trails. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence helps counterfeiters design sophisticated replicas, automate advertising campaigns and target consumers with personalized marketing. All of these tools combined enable criminal groups to replicate goods with growing speed and precision, and on a scale once reserved for legitimate suppliers.45

While these technological developments have undoubtedly contributed to the rapid sophistication of counterfeiting, the market must also be understood more broadly in the context of global macroeconomic turbulence.

The global economy is undergoing a profound transition, shaped by volatility in inflation, stagnating growth and heightened policy uncertainty.46 The inflationary cycle of the past three years illustrates these pressures. In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, prices briefly receded as demand collapsed and energy markets contracted. Yet this was quickly reversed: once restrictions eased, broken supply chains and resurgent energy costs, aggravated by events such as the Russo-Ukrainian war and exchange rate volatility, triggered sharp inflationary spikes. By mid-2022, worldwide inflation reached levels not seen since the 1990s. Although rates have moderated somewhat since, they remain well above historical norms.47 Projections now point to a renewed escalation in 2025, with tariff conflicts, higher energy prices and structural labour shortages expected to act as key inflationary drivers.48

This macroeconomic instability has eroded household purchasing power worldwide. Consumers face higher costs for essentials such as food, housing and energy, while wage growth lags behind, deepening consumer vulnerability. Global output is also slowing: the World Bank projects growth of just 2.3% in 2025, the weakest pace since 2008 outside of a formal global recession. The slowdown is particularly acute in developing economies, where nearly 60% are expected to experience significant deceleration, undermining job creation, poverty reduction and income convergence with advanced economies.49

Trade flows, once relatively resilient, are also set to contract. Global trade growth is projected at only 1.7% in 2025, a steep downward revision linked to tariffs applied to imports and geopolitical frictions.50 Labour markets reflect similar strains, with unemployment rates increasing, which is particularly affecting young job seekers.51 The combined effect is widening inequality and an uncertain global financial future.

Against this backdrop, counterfeiting has expanded. Consumers are increasingly price-sensitive. When faced with rising costs for legitimate products, many turn to counterfeit substitutes that offer the appearance of authenticity at lower prices. Affordability is the primary driver of demand for counterfeit goods.52 For many households, counterfeits are a coping mechanism in the face of financial pressure.

Changes in counterfeit trade by region (2023–2025)

Regional patterns in the Index indicate the heightened impact of this market. Areas where counterfeiting includes essential goods as well as pharmaceuticals consistently record higher average scores for market pervasiveness. Western Asia, for example, has experienced a sharp rise in its rankings, moving from third place in 2023 with an average of 6.14 to the highest-ranked region in 2025 with an average of 6.32. This shift is closely linked to the widespread circulation of counterfeit medicines, exacerbated by fragile healthcare systems in many states across the region.53 A comparable trend is visible in South-eastern Asia, which registers the same regional average and likewise has a pervasive market for counterfeit pharmaceuticals.54

Although they do not rank among the highest-scoring regions for this criminal market globally, North America (5.50) and Australia and New Zealand (2.50) registered the steepest increases since 2023, by 0.50 points each. Each region encompasses only two countries, which can exaggerate statistical shifts; nevertheless, the trend is striking. The key finding is not the absolute level of pervasiveness, which remains low to moderate, but the direction of change in these advanced economies, where counterfeiting was in the past less entrenched. In North America, the United States (6.50) and Canada (4.50) each recorded an increase of half a point, reflecting the rising prevalence of counterfeit goods in trade flows – a trend likely to be further amplified by the tariff disputes and trade frictions that have been unfolding in 2025. Australia (3.0), meanwhile, registered a full-point increase. One survey conducted in May 2025 estimates that as many as one in eight Australians have purchased counterfeit designer products from Chinese manufacturers.55 That such shifts are occurring in high-income, highly regulated markets is evidence that counterfeiting is no longer confined to emerging or fragile economies – it is becoming a structural feature of global trade, with implications for even the most developed states.

This regional picture also illustrates a deeper reality: counterfeiting rarely exists in isolation. The interconnectedness of the counterfeit trade extends beyond its ties to the licit economy and into the broader landscape of organized crime. The latest Index data shows that counterfeiting exhibits the highest correlation with other criminal markets globally, with a strong coefficient of 0.84. In practice, this means that countries with high levels of counterfeit activity tend to register a high presence of other criminal markets too, in which overlapping networks, routes and financial flows interconnect across criminal markets. The drivers behind this pattern are rooted in increasing economic instability, declining household purchasing power and constrained state resources. As individuals seek alternative sources of income amid financial hardship, participation in illicit markets becomes more attractive. At the same time, governments facing fiscal pressures struggle to maintain the institutional capacity required to disrupt criminal networks, reinforcing a cycle in which all forms of organized crime thrive.

Correlation coefficient between trade in counterfeit goods and criminal markets average (2025)

Together, these regional and systemic dynamics confirm that counterfeiting has moved well beyond the realm of imitation luxury goods. The market now sits at the intersection of three major disruptors: economic slowdown, technological transformation and trade frictions. Each reinforces the others, producing a feedback loop that amplifies the reach and resilience of the counterfeit economy. Understanding the scope, scale and changing characteristics of this market is therefore critical for policymakers, both in regions where counterfeit goods already threaten public health and safety, and in those where its presence is expanding rapidly.

2.4 Architects of criminal expansion

As highlighted throughout this report, criminal actors, particularly those acting as organized crime's facilitators, demonstrate a remarkable capacity for adaptation, exploiting global shifts from conflict and resource scarcity to evolving consumer preferences and technological advances in production. Much like the multi-headed Hydra, criminal groups adapt rapidly, capitalizing on emerging or deepening conflicts and aligning with digital developments. When one head is cut off, the organism regenerates, with new heads taking its place. Many of these transformations are most evident in the growing influence of two categories of actors: foreign criminal actors and the private sector.

Foreign actors registered the sharpest overall increase (+0.40 between 2021 and 2025), with West Africa standing out at 6.67 in 2025. Private sector actors experienced the steepest growth (+0.13 between 2023 and 2025), led by Western Asia at 6.43.

Evolution of criminal actors (2021–2025)

The rising prominence of these groups moves them closer to the forefront of organized crime, a domain long dominated by state-embedded actors. This does not suggest, however, that the latter have diminished in significance. On the contrary, state-embedded actors remain the most influential globally, as they have across all three iterations of the Index. But it shows how foreign and private sector actors are gaining ground in reshaping illicit economies, marked by a flexibility that enables them to bypass legal and regulatory barriers. The momentum behind this expansion is closely tied to fractured international relations, as eroding levels of global cooperation – an essential element in combating transnational organized crime – provides opportunities for transnational illicit networks to consolidate and grow.

Since 2023, foreign criminal actors – defined as criminal groups operating outside their countries of origin – have recorded the sharpest increase in pervasiveness globally (+0.14). Their role is often dual, acting both as facilitators and beneficiaries of illicit markets. Illicit goods or services rarely remain in one place; they are in constant motion along the criminal chain. To keep this movement alive, criminal groups rely on one another, whether for access to supplies, to secure transit routes, distribute goods or launder illicit profits. Out of this necessity, alliances take shape across regions, built less on loyalty than on pragmatism. Actors with different backgrounds and expertise from different regions come together, adapting their methods to the opportunities before them and the contexts in which they operate, prioritizing flexibility over rigid monopolistic control.

Foreign criminal actors by region (2025)

Transnational drug cartels are a prime example of this pragmatic approach to cooperation among foreign actors. This can be seen in the alliances formed between South American cartels and local groups in the Balkans. The success of Balkan networks has rested on their ability to collaborate with a wide range of partners, from Latin American suppliers and West African intermediaries to European distributors. Rather than attempting to dominate the entire chain, these networks have thrived by strategically inserting themselves at key points, cultivating a transactional reputation that positions them as 'reliable' partners.

These examples demonstrate that the strength of such actors lies in their pragmatic approach and willingness to forge alliances, arguably in stark contrast to states, which, in today's divisive global context, increasingly react in fragmented and individualistic ways in international forums and other engagements. While these traits are central to the growing influence of foreign actors, broader global shifts have also fuelled their expansion. Among these are the widening reach of criminal interests enabled by virtual spaces, such as cyber-enabled fraud, the escalation of conflicts as violent organizations compete for power and resources, the erosion of territorial integrity and the weakening of state capacity to monitor foreign businesses. Each of these vulnerabilities is exploited by actors whose hallmark flexibility enables them to adapt and thrive across shifting landscapes.

Under pressure – territorial integrity

Territorial integrity, one of the key resilience measures for keeping foreign actors at bay both physically and in cyberspace, has come under growing strain in recent years. The lifting of COVID-19 movement restrictions, the globalization of trade through expanding infrastructure facilities such as ports and airports, and intensified use of cyberspace have placed significant pressure on this indicator. Since the inception of the Index, ‘territorial integrity’ has dropped by 0.14. When combined with the growing influence of foreign actors, weakening levels of territorial integrity point to mounting vulnerability facing states as their territories become more exposed to the dynamics of interconnected illicit economies.

Foreign actors and territorial integrity, global average (2021–2025)

West Africa (6.67) stands out as the highest-ranking region globally in terms of the influence of foreign actors, whose presence permeates almost every strand of the criminal economy. The region's strategic location, resource wealth and institutional fragility make it particularly attractive to external actors, embedding foreign influence into local economies. Nigerian networks extend their influence far beyond their borders, driving human trafficking, fuel smuggling and cyber-enabled fraud in neighbouring states. Chinese actors have become embedded in resource economies, particularly illegal logging and informal mining. Latin American cartels and European networks have likewise made coastal West African hubs critical nodes for global cocaine routes. Meanwhile, private military company the Wagner Group – rebranded as Africa Corps – has been operating under the guise of security assistance, but in practice has been linked to looting, extortion and smuggling. Adding another layer of complexity, violent extremist organizations, including Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State Sahel Province, exploit illicit economies within the region by taxing traffickers, controlling smuggling routes and through involvement in the gold, fuel, arms and wildlife trade, while also presenting themselves as parallel governing authorities and service providers in neglected regions.

South-eastern Asia, a region where foreign actors dominate certain criminal markets, including counterfeit goods and environmental crimes, follows closely behind at 6.64. Demand for rare timber, wildlife products and illegally mined minerals has drawn significant foreign involvement, while international companies have been implicated in illegally laundering forest resources through global supply chains by reintegrating them into the legal trade. At the same time, foreign groups in the region maintain a strong presence in narcotics trafficking, using key regional hubs as gateways to high-value markets such as Australia and Europe, positioning South-eastern Asia as a central link in global drug chains. Diaspora communities also play a significant role in the region's illicit economies. In particular, Chinese networks operating in the region have been associated with activities ranging from illegal gambling and online scam operations to methamphetamine trafficking.

While illicit supply chains remain the primary arena of foreign actor influence, operations are no longer limited to physical infrastructure but increasingly extend into the digital space. Traditional criminal markets are shifting online, with transactions facilitated through e-commerce platforms and payments processed using digital systems and blockchain technologies. This shift has diminished the need to maintain a physical footprint in most criminal markets, including wildlife trafficking and the drug trade. The trend is most evident in cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled financial crimes, where perpetrators and victims are often separated by entire continents. The surge in large-scale cyber fraud has drawn attention to this trend, particularly since the exposure of cyber scam compounds in South-eastern Asia that have an impact in other regions. Specializing in defrauding victims in financially stable countries, these centres generate tens of billions of dollars annually. This globalization of illicit economies, facilitated by technology, has amplified the role of foreign actors, as physical borders no longer constrain these forms of criminality.

Alongside foreign actors, the private sector has also emerged as a growing conduit of illicit activities. Discussions of organized crime and the private sector have tended to focus on legitimate businesses as victims, highlighting the adverse impact of illicit markets on their operations. Yet it is increasingly evident that private sector actors should not be viewed only through this lens, as their involvement as perpetrators of organized crime is becoming harder to ignore. In fact, when it comes to forging alliances within illicit economies, private sector actors stand out as indispensable partners for all types of criminal groups. Their role, whether in logistics, finance or technology, has become increasingly pervasive, enabling the movement of illicit goods and the integration of criminal proceeds into the formal economy. The growing recognition of this role, long overlooked, is reflected in the 2025 Index, which recorded among the sharpest increase in influence for any actor type between 2023 and 2025 (+0.13). Yet despite this jump, private sector actors continue to rank on average as the least influential criminal actor category.

Private sector criminal actors by region (2025)

Private sector actors play a dual role in the criminal ecosystem. They can be direct perpetrators of criminal activities, including environmental crimes (such as illegal logging, mining and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing) as well as financial crimes – tax evasion, fraud, embezzlement and corruption. On the other hand, companies are co-opted as facilitators by organized criminal groups. In these cases, businesses may knowingly or unwittingly provide technology networks, documentation, logistical support or channels for laundering illicit funds through financial systems and real estate markets. It is in the latter role that their influence is most evident. By enabling logistics, financial flows and technological support, they embed themselves within broader criminal alliances, making them indispensable to the functioning of illicit economies.

2.5 Resilience at a crossroads: international cooperation and judicial systems under pressure

Resilience indicators largely reflect the effectiveness of institutional systems, such as law enforcement, prevention and criminal justice, where change is inherently slow-moving. As a result, shifts in resilience scores are less likely to produce sharp variations over short periods of time. This gradual pace of change is reflected in the global averages, which showed only a marginal movement of −0.004 points between 2021 and 2023, followed by a further −0.03 points between 2023 and 2025. At the continental level, changes have been similarly minimal, with the overall ranking remaining consistent since the Index's inception in 2021.

Evolution of resilience (2021–2025)

Nevertheless, an important shift has been observed in the Index's strongest-performing resilience indicator: 'international cooperation'. For three consecutive iterations, 'international cooperation' has outperformed the other 11 resilience indicators, with average scores of 5.68 in 2021, 5.87 in 2023 and 5.90 in 2025, underscoring what has been a broad trust in the international legal system and a past propensity among sovereign states to engage in cooperative frameworks. This cooperative momentum was particularly visible in earlier years of the Index, when law enforcement collaboration, technical assistance and bilateral agreements contributed to marked gains. Indeed, the second iteration of the Index recorded the highest single increase for 'international cooperation' of all 12 resilience indicators. However, this trajectory slowed considerably in 2025, registering only a marginal 0.03 point increase since 2023. This suggests the indicator may have plateaued, raising questions about whether the trend of improvement in international cooperation has reached its peak. For international cooperation, we may have reached a potential inflection point.

The timing is noteworthy. The first two iterations of the Index followed a period in which shared global challenges – the COVID-19 pandemic and its socio-economic consequences, intensifying conflicts and the climate crisis – fostered a sense of collective responsibility among states, even those with diverging political agendas. In contrast, the past two years have witnessed a reversal: national interests increasingly taking precedence over the common good. Illustrative examples include:

- Russia's withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights in September 202256 and its revocation of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in November 2023.57 Russia's score for this indicator is 3.0 – down from 4.50 in 2021.

- Nicaragua's exit from the Organization of American States in November 2023.58 Nicaragua's score is 2.0 – down from 2.50 in 2021.

- The coordinated decision of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger to withdraw from the Economic Community of West African States in January 2024, coupled with their distancing from traditional Western alliances, including the expulsion of French and US forces.59

The latter case triggered one of the sharpest declines in regional international cooperation scores since 2023 as West Africa's average fell by 0.27 points to 5.17. This drop was largely attributable to Burkina Faso (down by 1.50 points to 3.50), Mali (by 1.0 point to 3.0), and Niger (by 2.0 points to 3.50) – countries that were among those registering the steepest declines globally in this resilience indicator in 2025.

International cooperation by region (2021–2025)

Since early 2025, more states, including the US, have announced plans to withdraw from international courts, organizations and treaties, a trend reflecting perceptions of multilateral institutions as overly interventionist. While these developments fall outside the scope of the data that informs this iteration of the Index, they signal a deepening shift toward unilateralism that warrants close monitoring in the years ahead.

If such decisions materialize and similar patterns continue, international cooperation could reach a critical turning point. Multilateral cooperation has long been central to confronting illicit economies that operate across borders, yet the growing drift toward unilateralism threatens to undermine this foundation. Weakening trust and solidarity between states reduces the system's ability to contain networks whose influence extends beyond national jurisdictions. The findings of the 2025 Index corroborate this trend, recording the sharpest global increase in foreign actors among criminal groups. As discussed above, these actors are steadily consolidating their position as some of the most influential drivers of organized crime, embedding themselves in multiple markets and regions. Such developments highlight the structural interconnectedness of illicit economies and suggest that, in the absence of strong cooperative mechanisms, resilience levels are likely to erode further, accompanied by mounting criminality worldwide.

Another notable shift has been observed in the 'judicial system and detention' indicator, which recorded a deterioration of −0.12 points since 2023 – the sharpest decline across all resilience indicators in 2025. As the final and decisive stage of the criminal justice process, the judiciary plays a pivotal role in addressing organized crime. It adjudicates cases, imposes penalties that carry both punitive and deterrent weight, and ensures that justice is delivered in a credible manner. By setting the framework for investigation, prosecution and adjudication, the judiciary underpins accountability and safeguards the rule of law, making it an indispensable pillar in the fight against organized crime.

Penitentiary systems play an equally vital role, both in disrupting organized crime and in preventing its reproduction. Effective detention regimes can dismantle criminal leadership structures, hinder operational networks and serve a rehabilitative function, enabling the reintegration of offenders into society.

Despite their importance, this indicator has consistently performed poorly under the Index. Since its inception, 'judicial system and detention' has ranked among the four weakest resilience indicators, trailing 'victim and witness support' and 'government transparency and accountability' in the past two iterations, with average scores of 4.59 in 2021, 4.54 in 2023 and 4.42 in 2025. The recent decline is therefore especially concerning, as it reflects weakness in an institution that is essential to sustaining long-term resilience to organized crime.

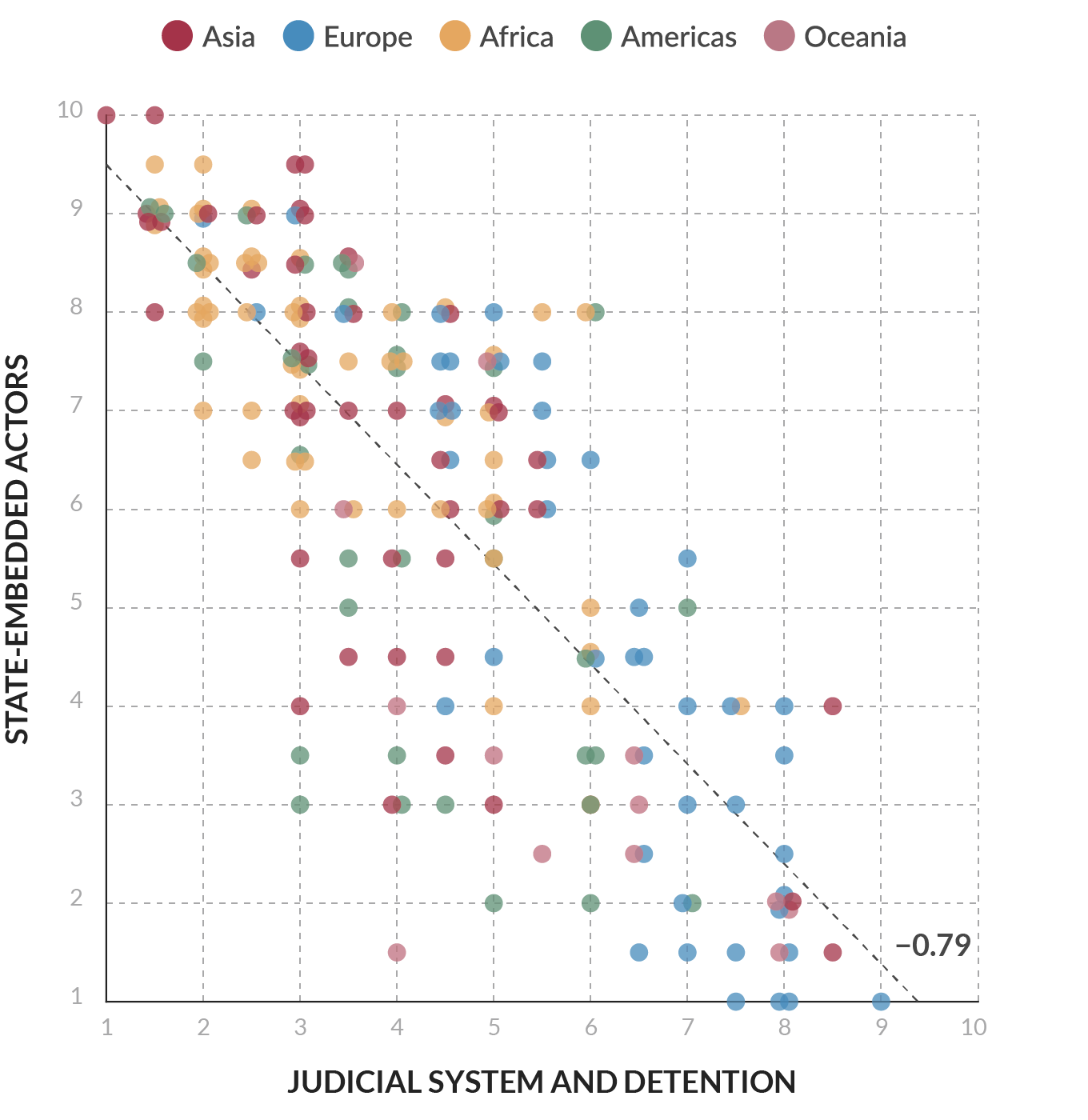

Correlation coefficient between state-embedded actors and judicial system and detention (2025)

This declining strength in the judicial and penitentiary systems is compounded by the strong correlation between state-embedded actors and the performance of the judicial system. With a coefficient of −0.79, the 'judicial system and detention' indicator is among the most adversely affected by corruption within state institutions, ranking just behind the 'leadership and governance’ indicator. This figure is not only statistically significant, but also points to a structural vulnerability: when state actors are themselves involved or complicit in organized crime, the very institutions tasked with upholding justice become compromised, undermining their ability to address the problem effectively.

Corruption, political interference and selective enforcement of the law erode judicial independence, weaken prosecutorial capacity and distort sentencing practices. Penitentiary systems, rather than serving as spaces for disruption and rehabilitation, can instead become extensions of criminal networks, allowing actors to exert influence, secure privileges or even direct criminal operations from within prison walls. The outcome is a dual failure: the judiciary and detention systems lose their deterrent power while simultaneously reinforcing impunity for those with access to political protection. Taken together, the decline observed in 2025 should be seen as more than a statistical fluctuation: it is a warning sign of how state capture and institutional weakness can converge to erode one of the most critical pillars of resilience.

Notes

- 1.See UNODC, World Drug Report 2025, Key findings, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR_2025/WDR25_B1_Key_findings.pdf.

- 2.Ibid., p. 48.

- 3.Vanessa Buschschlüter, Colombia cocaine: Coca cultivation reaches record high, BBC, 12 November 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-66784678.

- 4.US Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration, National Drug Threat Assessment 2024, p. 16, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2024-05/NDTA_2024.pdf.

- 5.European Union Drug Agency, Cocaine – the current situation in Europe, European Drug Report 2024, https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2024/cocaine_en.

- 6.UNODC, Uncovering synthetic drug production: UNODC launches new module on Advanced Investigative Techniques , 2023, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2023/March/uncovering-synthetic-drug-production_-unodc-launches-new-module-on-advanced-investigative-techniques.html.

- 7.International Narcotics Control Board, Precursors and chemicals frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, E/INCB/2023/4, p. 16 onward, https://unis.unvienna.org/unis/uploads/documents/2024-INCB/E_INCB2023_Precursors.pdf.

- 8.Calculated on the basis of the number of countries scoring 5.50 or higher for that indicator (i.e. 96 out of 193).

- 9.United Nations News, 'Rapid expansion' of synthetic drugs reshaping illicit markets, UN anti-narcotics body warns, March 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/03/1160741.

- 10.Brookings, The fentanyl epidemic in North America and the global reach of synthetic opioids, https://www.brookings.edu/collection/the-fentanyl-epidemic-in-north-america-and-the-global-reach-of-synthetic-opioids/.

- 11.Syria has long been a major Captagon production and trafficking hub. See Conor Lennon, Despite the fall of Assad, the illicit drug trade in Syria is far from over, UN News, 26 June 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/06/1164696.

- 12.Mohammed Rasool, This drone full of meth shows Syria's narco traffickers are diversifying, VICE, August 2023, https://www.vice.com/en/article/jordan-syria-drone-crystal-meth-captagon/.

- 13.David Hutt, Inside Southeast Asia's surging meth trade, DW, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/inside-southeast-asias-surging-meth-trade/a-73066620.

- 14.Daniel Brombacher and Ruggero Scaturro, Highly potent synthetic opioids are already in Europe's drug supply chains, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), 2024, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/highly-potent-synthetic-opioids-are-already-in-europes-drug-supply-chains/.

- 15.UNODC, World Drug Report 2025, Key findings, p. 66, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR_2025/WDR25_B1_Key_findings.pdf.

- 16.Anine Kriegler, Cannabis policy reform and organized crime: A model and review for South Africa, GI-TOC, 2024, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/cannabis-reform-organized-crime-south-africa/.

- 17.Maria Khoruk, Smoke and mirrors: Afghanistan’s illicit drug economy after the opium ban, GI-TOC, 2025, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/afghanistans-illicit-drug-economy-after-the-opium-ban/.

- 18.European Drug Trends Monitor, Issue 1, GI-TOC, December 2024, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Observatory-of-Organized-Crime-in-Europe-European-Drug-Trends-Monitor-Issue-1-GI-TOC-December-2024.v4.pdf.

- 19.Markus Schultze-Kraft, Organised crime, violence and development, Topic guide, GSDRC, August 2016, https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/organised-crime-violence-development/organised-crime-and-violence-and-instability/#:~:text=when%20it%20comes%20to%20criminal,to%20obtain%20redress%20for%20grievances.

- 20.Compound Crime: Cyber scam operations in Southeast Asia, GI-TOC, May 2025, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/compound-crime-cyber-scam-operations-in-southeast-asia/.

- 21.Colin Murphy, Understanding cybercrime, European Parliamentary Research Service, 2024, p. 2, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/760356/EPRS_BRI(2024)760356_EN.pdf.

- 22.INTERPOL, Cybercrime: When cybercriminals go global, our response must be international, https://www.interpol.int/Crimes/Cybercrime.

- 23.Ibid.

- 24.Ibid.

- 25.In the Index methodology, Australia and New Zealand are treated as a region.

- 26.World Economic Forum, The Global Risks Report 2024, 19th edition, January 2024, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2024.pdf.

- 27.Council of Europe action against Cybercrime, Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/coe-action-against-cybercrime.

- 28.Robert Muggah and Mac Margolis, Why we need global rules to crack down on cybercrime, World Economic Forum, January 2023, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/01/global-rules-crack-down-cybercrime/.

- 29.Cyber Management Alliance, Major cybersecurity challenges in the age of IoT, February 2025, https://www.cm-alliance.com/cybersecurity-blog/major-cybersecurity-challenges-in-the-age-of-iot#:~:text=As%20vulnerability%20continues%20to%20manifest%20in%20IoT,cybersecurity%20challenges%20in%20the%20Age%20of%20IoT.

- 30.ICLG, Cybersecurity laws and regulations Denmark 2025, November 2024, https://iclg.com/practice-areas/cybersecurity-laws-and-regulations/denmark#:~:text=The%20next%20step%20for%20cybersecurity,organisations%20to%20combat%20transnational%20threats.

- 31.GSDRC, Organised crime and violence and instability, August 2016, https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/organised-crime-violence-development/organised-crime-and-violence-and-instability/#:~:text=when%20it%20comes%20to%20criminal,to%20obtain%20redress%20for%20grievances.

- 32.Transcrime, Study on extortion racketeering: The need for an instrument to combat activities of organised crime, https://www.transcrime.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Study_on_extortion_racketeering-Final_Report.pdf.

- 33.UNODC, How effective firearms control can reduce violence and promote peace, UNODC, 2025, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/firearms-protocol/news/2025/how-effective-firearms-control-can-reduce-violence-and-promote-peace.html#:~:text=A%20vicious%20circle,lack%20of%20control%20over%20them.

- 34.Center for Preventive Action, Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, June 2025, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo.

- 35.In the wake of the Sudan conflict, fuel and arms smuggling spike in Chad and the broader Sahel, GI-TOC, Risk Bulletin 8, August 2023, https://riskbulletins.globalinitiative.net/wea-obs-008/01-in-the-wake-of-the-sudan-conflict-fuel-and-arms-smuggling-spike.html.

- 36.Gabon will see increased political stability in coming months, BMI (Fitch Solutions), June 2025, https://www.fitchsolutions.com/bmi/political-risk/gabon-will-see-increased-political-stability-coming-months-04-06-2025#:~:text=Gabon%20will%20see%20increased%20political%20stability%20in%20the%20coming%20months,two%20years%20of%20military%20rule.

- 37.Carnegie Corporation of New York, Who arms the world's conflicts?, June 2022, https://www.carnegie.org/our-work/article/who-arms-the-worlds-conflicts/#:~:text=The%20eleven%20top%20suppliers%2C%20listed,Emerging%20Global%20Order.

- 38.GI-TOC, Smoke on the horizon: Trends in arms trafficking from the conflict in Ukraine, June 2024, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/trends-arms-trafficking-conflict-ukraine-russia-monitor/.

- 39.Emilio Parodi, Insight: Turning its back on extreme violence, Italy's mafia mastered white collar crime turning over billions in dirty money, AML Intelligence, May 2024, https://www.amlintelligence.com/2024/05/insight-turning-its-back-on-extreme-violence-italys-mafia-mastered-white-collar-crime-turning-over-billions-in-drity-money/.

- 40.Isabel Sanchez, In Peru, gangs intensify violence and extortion, The New York Times, June 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/10/world/americas/peru-gang-violence-extortions.html.

- 41.EUROPOL, Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment 2025: Steal, deal and repeat – How cybercriminals trade and exploit your data, 2025, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Steal-deal-repeat-IOCTA_2025.pdf.

- 42.OECD, Global trade in fake goods reached USD 467 billion, posing risks to consumer safety and compromising intellectual property, press release, May 2025, https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2025/05/global-trade-in-fake-goods-reached-USD-467-billion-posing-risks-to-consumer-safety-and-compromising-intellectual-property.html.

- 43.Corsearch, Trade in counterfeit goods market set to reach $1.79 trillion in 2030, press release, May 2024, https://corsearch.com/about/press-releases/trade-in-counterfeit-goods-market-set-to-reach-1-79-trillion-in-2030/.

- 44.Brandtag, The global counterfeit crisis, June 2024, https://brandtag.io/2024/06/17/the-global-counterfeit-crisis-understanding-the-scope-and-impact/.

- 45.Merilee Kern, AI driving U.S. luxury goods counterfeit crisis, new study finds – Part 1, Resident, April 2025, https://resident.com/insights-and-perspectives/2025/04/10/ai-driving-us-luxury-goods-counterfeit-crisis-new-study-finds-part-1.

- 46.Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, IMF Blog, The global economy enters a new era, April 2025, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2025/04/22/the-global-economy-enters-a-new-era.

- 47.World Bank Group, What explains global inflation?, Brief, July 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/global-inflation?.

- 48.World Bank Group, Global economy set for weakest run since 2008 outside of recessions, press release, June 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/06/10/global-economic-prospects-june-2025-press-release.

- 49.Ibid.

- 50.Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, IMF Blog, The global economy enters a new era, April 2025, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2025/04/22/the-global-economy-enters-a-new-era.

- 51.International Labour Organization, Global unemployment rate set to increase in 2024 while growing social inequalities raise concerns, says ILO report, January 2024, https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/global-unemployment-rate-set-increase-2024-while-growing-social.

- 52.EUIPO, European citizens and intellectual property: Perception, awareness and behavior, 2023, p. 11, https://www.euipo.europa.eu/en/news/perception-study-half-of-young-consumers-find-it-acceptable-to-buy-fakes?utm.

- 53.Sarah Fares and Laura Adal, Fake drugs, real impact: Western Asia's counterfeit medicine epidemic, GI-TOC, September 2023, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/western-asia-counterfeit-medicine/.

- 54.Nick Redfearn, Pharma and consumer health product counterfeiting across South East Asia, Rouse, January 2023, https://rouse.com/insights/news/2023/pharma-and-consumer-health-product-counterfeiting-across-south-east-asia.

- 55.Taylor Blackburn, Cheap fakes: 1 in 8 Aussies buying counterfeit luxury goods straight from China, Finder, July 2025, https://www.finder.com.au/news/aussies-buying-counterfeit-luxury-goods-2025.

- 56.Council of Europe, Russia ceases to be party to the European Convention on Human Rights, Council of Europe Newsroom, September 2022, https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/russia-ceases-to-be-party-to-the-european-convention-on-human-rights.

- 57.United Nations, Secretary-General deeply regrets decision by Russian Federation to revoke its ratification of Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm22022.doc.htm.

- 58.Wilfredo Miranda Aburto, The Ortega regime has officially withdrawn Nicaragua from the OAS, El País, November 2023, https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-11-21/the-ortega-regime-has-officially-withdrawn-nicaragua-from-the-oas.html?.

- 59.Bate Felix, David Lewis and Giulia Paravicini, West Africa's 'Brexit' moment spells trouble for the region, Reuters, January 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/west-africas-brexit-moment-spells-trouble-region-2024-01-30/.